Blackface Shaped Europe’s Image of America

I wrote the full version of this article on James Joyce’s Ulysses for Modernism/modernity in 2023, “Lynching Modernism: Ulysses, America, and the Negro Minstrel Abroad.” That piece grew out of work I originally produced for two graduate seminars: an essay on blackface in Joyce’s Ulysses for Dr. Rebecca Walkowitz’s 2017 class, and an essay on European representations of lynching for Cheryl Wall’s 2018 class.

My core research question was simple: why does a high-modernist novel set in Dublin—a novel with zero Black characters—use the N-word so often? Why does an Irish novel contain so many references to American racism and racial iconography?

The answer I arrived at has everything to do with the global cultural imaginary surrounding the United States.

Read the full article here: https://modernismmodernity.org/articles/ozier-lynching-modernism-ulysses-america-negro-minstrel-abroad

The Moment Joyce Goes Full Horror Show

From Chapter 15 of James Joyce’s Ulysses:

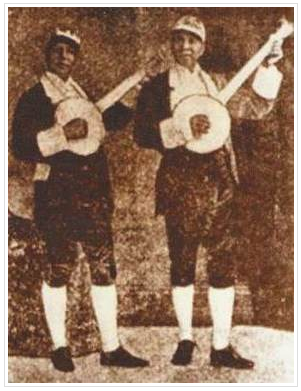

(Tom and Sam Bohee, coloured coons in white duck suits, scarlet socks, upstarched Sambo chokers and large scarlet asters in their buttonholes, leap out. Each has his banjo slung. Their paler smaller negroid hands jingle the twingtwang wires. Flashing white Kaffir eyes and tusks they rattle through a breakdown in clumsy clogs, twinging, singing, back to back, toe heel, heel toe, with smackfatclacking nigger lips.)

TOM AND SAM:

There’s someone in the house with Dina

There’s someone in the house, I know,

There’s someone in the house with Dina

Playing on the old banjo.(They whisk black masks from raw babby faces: then, chuckling, chortling, trumming, twanging, they diddle diddle cakewalk dance away.)

You do not need to know anything about Ulysses by James Joyce (1918 - 1920) to understand this moment. All you need is the image.

Bloom, the main character, walks into a brothel and begins hallucinating. Suddenly two Black performers appear from nowhere: Tom and Sam Bohee. They were famous nineteenth-century Black banjoists whose shows circulated throughout Europe. Their real names were James and George. Joyce names them Tom and Sam to make a pun -- Tambo and Sambo, two blackface minstrel archetypes.

Tambo and Sambo arrive dressed “in white duck suits” with “upstarched Sambo chokers” and “large scarlet asters.” Joyce describes their “flashing white kaffir eyes and tusks” and their “paler smaller negroid hands.”

The performers break into a “breakdown,” a term taken from minstrel performance vocabulary.

Then, they “whisk black masks from raw babby faces” and “diddle diddle cakewalk dance away.”

Two performers peel off their own black faces to reveal a paleness underneath. Joyce compresses the entire history of blackface spectacle and international entertainment culture into one violent theatrical gesture.

He rips a mask open.

Why Joyce Turns Minstrelsy Into Body Horror

Someone who has never read Ulysses might assume Joyce is doing this for shock value. There is a deeper logic.

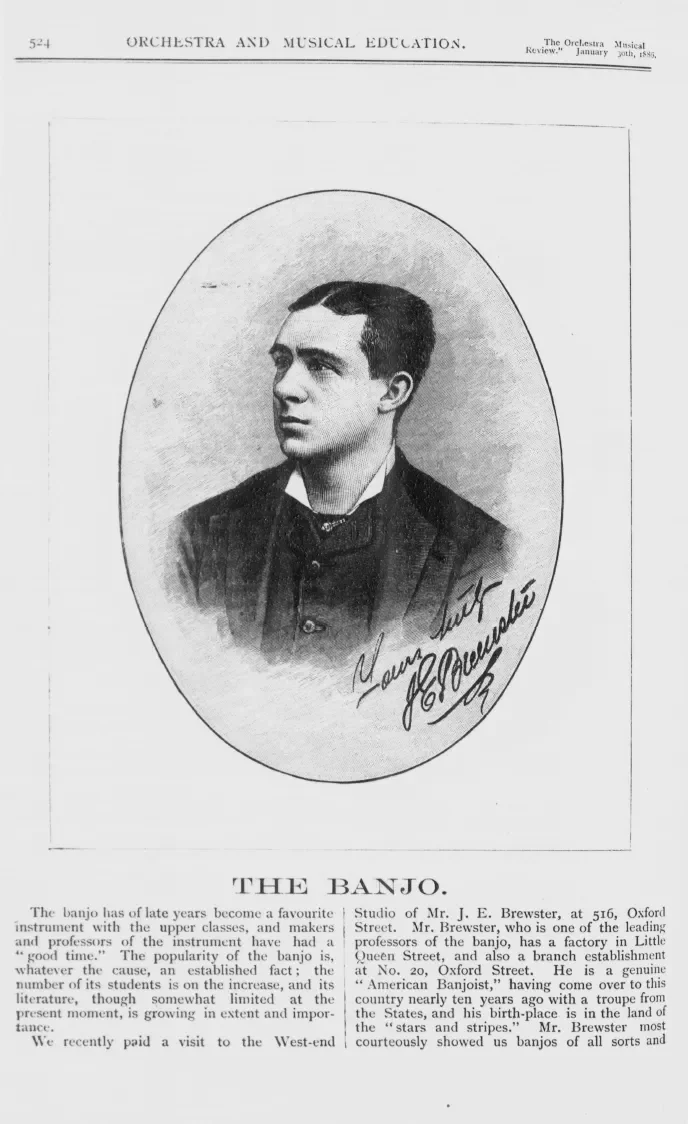

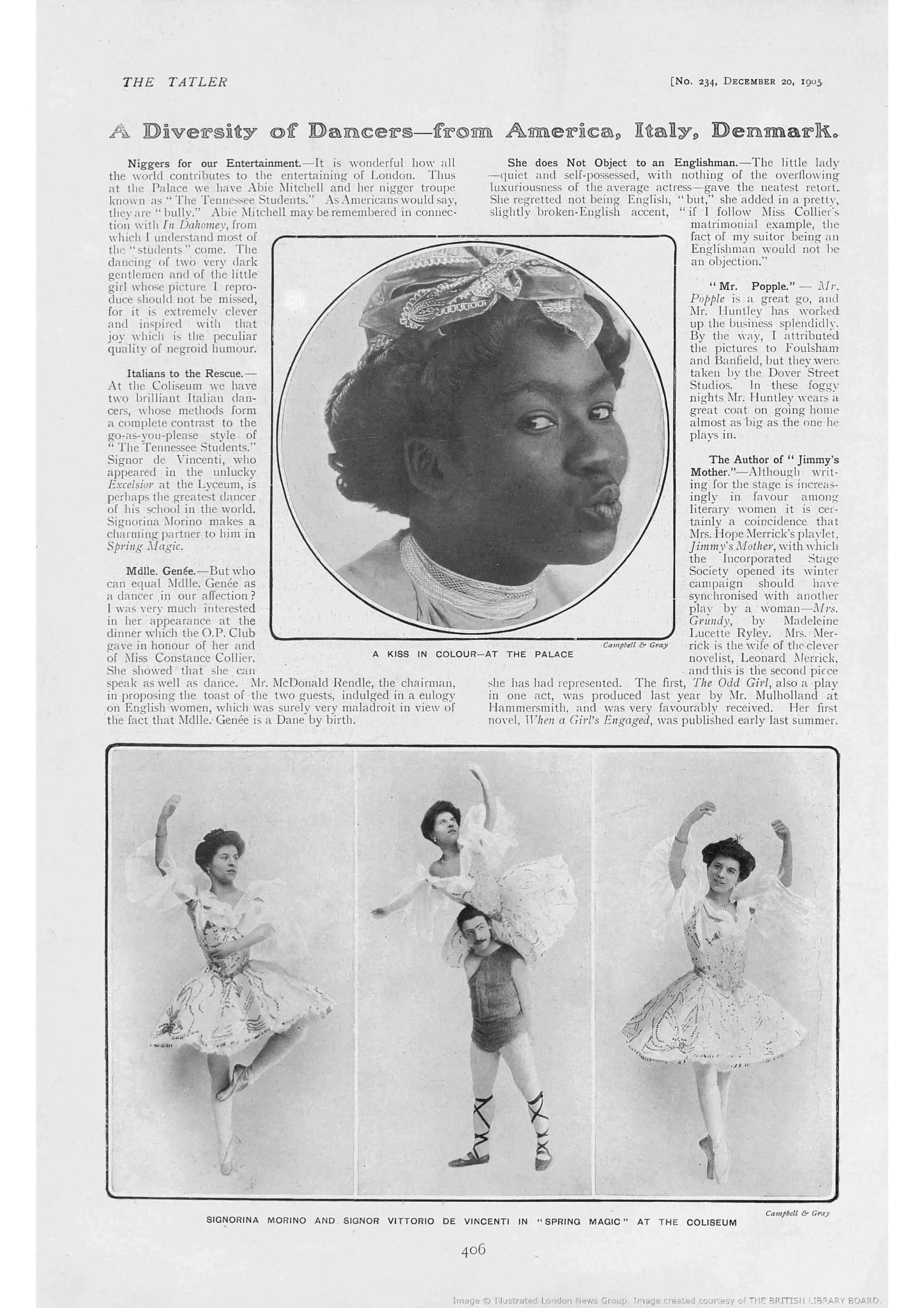

Minstrelsy was never a local American form. Joyce had absorbed the global traffic of Black performance and Black caricature that circulated through Ireland, Britain, and the United States. British companies advertised their performers as “real n—s of the old Dominion.” Banjo sellers marketed themselves as “genuine ‘American Banjoists’” and even bragged that their banjo wood was “imported from the States.” European composers claimed that the “future music” of America must be built on “Negro melodies,” which they described as the nation’s soil.

Joyce enters that world of cultural borrowing with precision. He stages the Bohee Brothers as symbols of a global entertainment industry that turned Blackness into something that could be costumed, packaged, sold, and consumed across continents.

Joyce uses racial performance as a site for experimenting with “shock, disgust, erotic transformation, and unstable bodies.” The disordered sexuality and bodily mutations that follow begin with the violent removal of a minstrel mask.

What This Scene Reveals About How Europe Understood Blackness

Europeans repeatedly used Black American culture to define what “America” was. Many readers assume this comes from jazz or the Harlem Renaissance. The process began much earlier.

Nineteenth-century British audiences had been trained to think of the United States through minstrel performance. Plantation caricature became shorthand for Americanness. The banjo became an American national instrument. White Irish, English, and Jewish performers used blackface to stabilize their own place in whiteness. Their performances helped convince audiences that race itself was a costume that could be put on or taken off at will.

Joyce is writing about the global structure that made Blackness into an international visual language.

Why This Moment Matters Today

Joyce is revealing how racial imagery travels, how violence becomes visual culture, and how Europe constructed its understanding of the United States through Black suffering and Black entertainment.

The Bohee Brothers’ scene in Ulysses exposes the theatricality of race. It reveals how minstrelsy shaped the European imagination and shows how modern writing was built on images of racial spectacle.

Joyce understood modernity as something built out of global racial exchange. The grotesque moment when performers rip their own faces off is not satire and not parody. It is a glimpse into the structural role of Black performance in the making of modern culture.

It is the mask behind the mask.

Read the full article here: https://modernismmodernity.org/articles/ozier-lynching-modernism-ulysses-america-negro-minstrel-abroad